Kiyoshi Suzuki - Soul and Soul 1969 - 1999

Photocopied trial cover for Mind Games, 1982

Soul and Soul 1969 - 1999

(published by Noorderlicht on the occasion of Suzuki's retrospective exhibition in 2008)

Kiyoshi Suzuki’s work moved me from the moment I first saw it. From the early 1990s onward I’ve exchanged many photobooks with publisher Kazuhiko Motomura. I sent him every possible photobook from Europe and the U.S., and he sent me Japanese books. One day, a box arrived with all eight books by Kiyoshi Suzuki. I remember taking them out and glancing through them—I felt as if I had entered someone’s private home, where everything I saw spoke to a very personal history which the viewer was invited into, slowly but surely.

The silence in Soul and Soul. The covers of Mind Games and S Street Shuffle. The many layers in Durasia. Many things stood out right away.

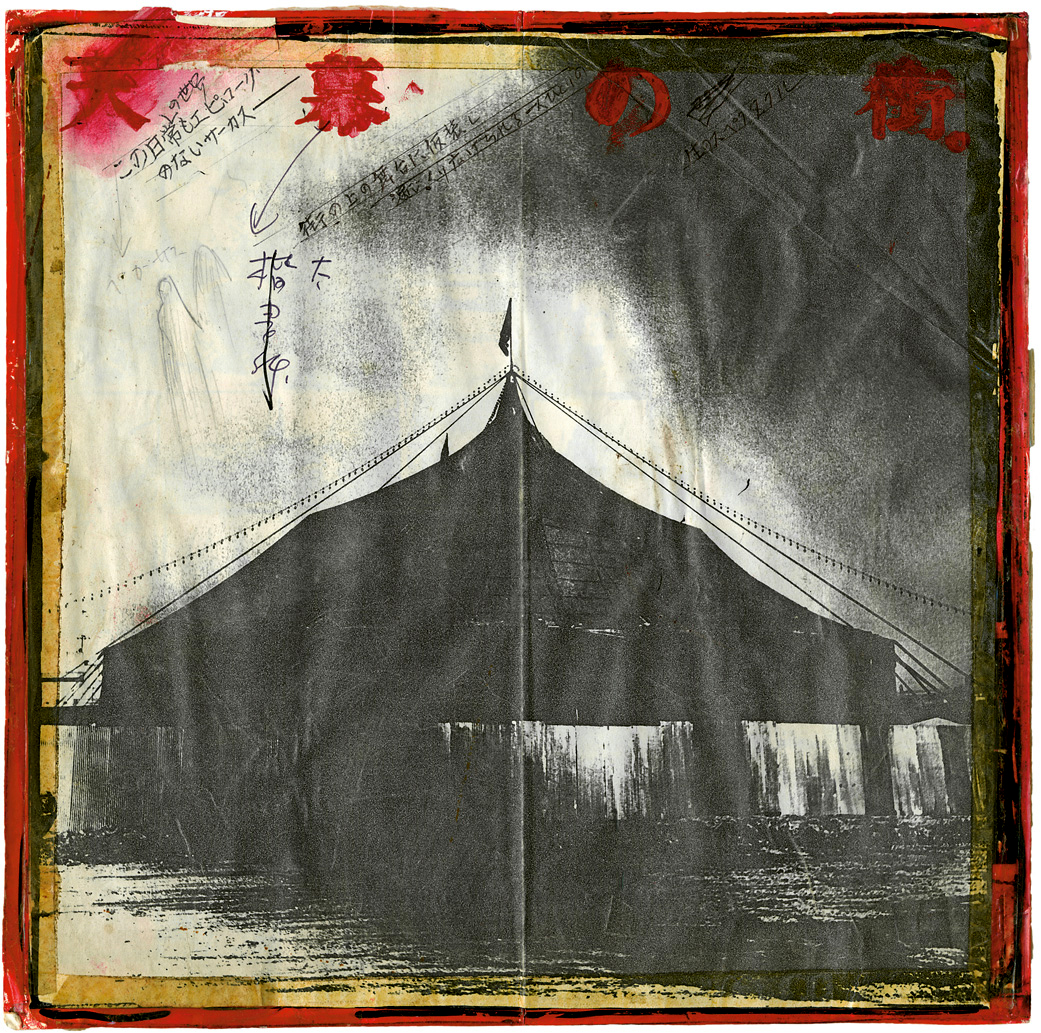

Soul and Soul was Suzuki’s first book, published in 1972. It is so beautifully dark and it has remarkable coherence. You wander around inside a highly obscure world and suddenly, the photographer begins to appear from out of nowhere. You sense him, you feel him. It is what the best photography does. Soul and Soul is a masterful first book—the Japanese title Nagare No Uta means Song of Drifting / Song of Floating / Song of Wandering. It belongs in the select company of the simply beautiful first book, like La Banlieue de Paris by Robert Doisneau, A Dialogue with Solitude by Dave Heath, Children of Europe by David Seymour, The Sweet Flypaper of Life by Roy DeCarava, to name a few.

In 1999 I co-curated Noorderlicht's main Festival exhibition, that was called Wonderland. One of the thirty participating photographers was Kiyoshi Suzuki, who I met in Tokyo to discuss selections from Soul and Soul and Mind Games. We spent some hours in the library of Gallery Mole, he was a kind man who liked my selections. A year later I was shocked to hear of his sudden passing.

In 2005/2006 I was planning another visit to Japan, mostly to meet with Miyako Ishiuchi to discuss the possibility of a retrospective exhibition in Langhans Gallery in Prague. Some years before I had become friends with Shin Kajimura, a rare photobook seller in Saitama, in the north of Tokyo. Shin was very much part of this planning and he suggested why not look at Suzuki as well. At the same time Noorderlicht asked me to curate an exhibition for the gallery, things fell into place without much effort.

There was a meeting, somewhere in a high building in Shibuya, with Yoko Suzuki and her daughter Yu, Kazuhiko Motomura and Shin Kajimura. I explained my ideas, which were not very precise and came down to me wanting to see all of Suzuki's work. Where it did become more precise is when I asked if he had many bookdummies for all his books and if they were still there. Yoko had been very quiet until then with a rather concerned expression, but when she heard the word bookdummy her eyes lit up smiling and she said in English: "many, many bookdummies!!". All four of us began to laugh, and I think each one must have thought the same. We were going to be fine.

It took two more trips and many visits to Yokohama, to go through Suzuki's prints, collages, bookdummies and many other things that were part of the workprocess of this photographer. The daughters Yu and Hikari became very involved, so did two former students of Kiyoshi, Isoko and Yuko. During the last visit we moved all the prints and other material to the gallery workspace of Masao Okubo, who so kindly let us work in there for almost a week.

The dummy for Soul and Soul surfaced during the search through Suzuki's estate. It was bound by hand, and much larger than the ultimate book. Suzuki had drawn the cropping for the smaller format of the book as it was ultimately published right into the larger book: a book within a book. One sees here the small beginnings of the great game that he would later be playing; in the knowledge that his later work would become one enormous explosion of book making, one can ask oneself if he was anticipating things. Whatever the case, the dummy is not only an object of great beauty, but in retrospect it is also one of the foundations for Suzuki's way of working. We found this dummy at the very end of that visit, it was so obvious how much seeing this object meant to Yoko. We all make our first book only once, and I am sure this also counts for those who live with the photographer. Glancing through this dummy I knew it held the direction for the exhibition and the book we were going to make. Yoko let me take it with me to Europe, a greater trust could not exist. At the time I lived in Italy, I had that dummy there for almost a year. It became almost a ritual to go through it, sometimes every day of the week and often first thing in the early morning. On many spreads Suzuki had written something. Of course I had no idea what it said. First I thought to scan these notes and ask Shin to translate. But I didn't. Perhaps I wanted to find out how far I would get by just looking at these pages, sometimes comparing with the published book. It was obvious Suzuki was re-interpreting an important part of an episode in his earlier life and I guess he was about 25 years old when doing this. So whatever it was, he was going back into his childhood. The images held nothing linear, he had not made an A to Z story. I could see some of the places were related to mining, but the images and the sequencing made one thing clear: it was not a book about mining. The feeling the images gave me was almost as if he had made these photographs when very young. From the perspective of a 10 to 15 year old boy. But a rather strange boy. I entered a dark, sometimes obscure world that seemed more animation and cartoon than photography as I knew it.

(With photography as I knew it I do not only mean classic photography, like Paul Strand or the likes. Perhaps I mean even more photographers like Moriyama. His first books are from around the same years as Soul and Soul. Also Moriyama is non linear. And some of his early images have a great sensitivity about them. But Moriyama, in Goodbye Photography and A Hunter is a collector of many small moments in passing. It is film and explosive. Suzuki's work is often as obscure and as dark, but it contains a psycological urgency and it has a meditative quality. That surfaces in the images, of course, but it is Suzuki's sequencing that connects the normal 'above ground' life to an under ground life)

Suzuki had gone back to what had fascinated him when he was a young boy. Dark faced men, often nude. Nude for cleaning. Objects that played a role under ground, maybe young Kiyoshi had wondered endlessly about what these dark faced men were meeting under ground. I would have.

Sometimes the work felt like a family album, with pictures of small brothers and sisters wanting to stand in front of the photographer and his camera. Sometimes there was theater, sometimes there are actors and actresses, but in his sequencing of the images they don't play any performance, they play a part of Kiyoshi's life. He is not only photographing, recording these people, he is also directing them. The book ends with the image of his sister's false eyelashes in a copper bowl, which is also the cover image of the book.

(When Daido Moriyama was installing his 2006 exhibition in Foam in Amsterdam, their director and the curator asked if I wanted to come and meet him. The same day we were sitting in Foam's café, six or seven Japanese and me around a table. Moriyama, through an interpretor, asked me what I was doing in Japan and I told him about Ishiuchi and Suzuki. He smiled and said something Suzuki-san and something else. He was quite exited. The interpretor turned to me and told me she did not understand him. She went to him again and he repeated his words. "The bowl" he is telling me, but I do not know what it means. How could she. But I knew, Moriyama meant the cover image of Soul and Soul. He put his thumb up, saying: "great image". Daido Moriyama later on, when I asked if he could write something in the Noorderlicht catalog, contributed very heartfelt words to this book about Kiyoshi Suzuki).

I wasn’t alone in making the decisions about using the dummy as inspiration for the resulting publication—I first consulted Shin Kajimura. Noorderlicht’s director Ton Broekhuis and curator Wim Melis agreed with the concept of using the photographer’s dummy as a foundation for the book. They suggested designer Hans Miedema. A small group of people helped Hans and me throughout the project: exhibition designers Ype van Gorkum, Marco Wiegers, and Olaf Veenstra and the writer Eddie Marsman. The goal of the catalog was to look and feel like the dummy of Soul and Soul. I also cleared the idea with Suzuki’s family, Yoko, Yu, and Hikari Suzuki, asking permission to reshuffle it a little, so that within the structure of that dummy, we would feature images from each of Suzuki’s other projects. This presents the work in a nonlinear manner, based more on a subjective, personalized vision, which seemed appropriate to the nature of Suzuki’s work.

The exhibition in the gallery of Noorderlicht opened in march 2008, it was liked a lot. The book came out with it and had the same response. Now, in may 2012, the second edition of Soul and Soul 1969 - 1999 is selling out.

The exhibition was also shown in the House of Photography at the Deichtorhallen, Hamburg in a remarkable presentation: their large central exhibition space was turned into a visual library for Kiyoshi Suzuki's eight books. Each book could be touched and seen by the visitors. Surrounding this central hall, on the outside of its walls, were shown the hundreds of Suzuki's original prints. I have yet to see a more democratic way to exhibit photography books.

In 2010 the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo exhibited the work of Kiyoshi Suzuki and published a catalog named Suzuki Kiyoshi: Hundred Steps and Thousand Stories. Also shown in this website.

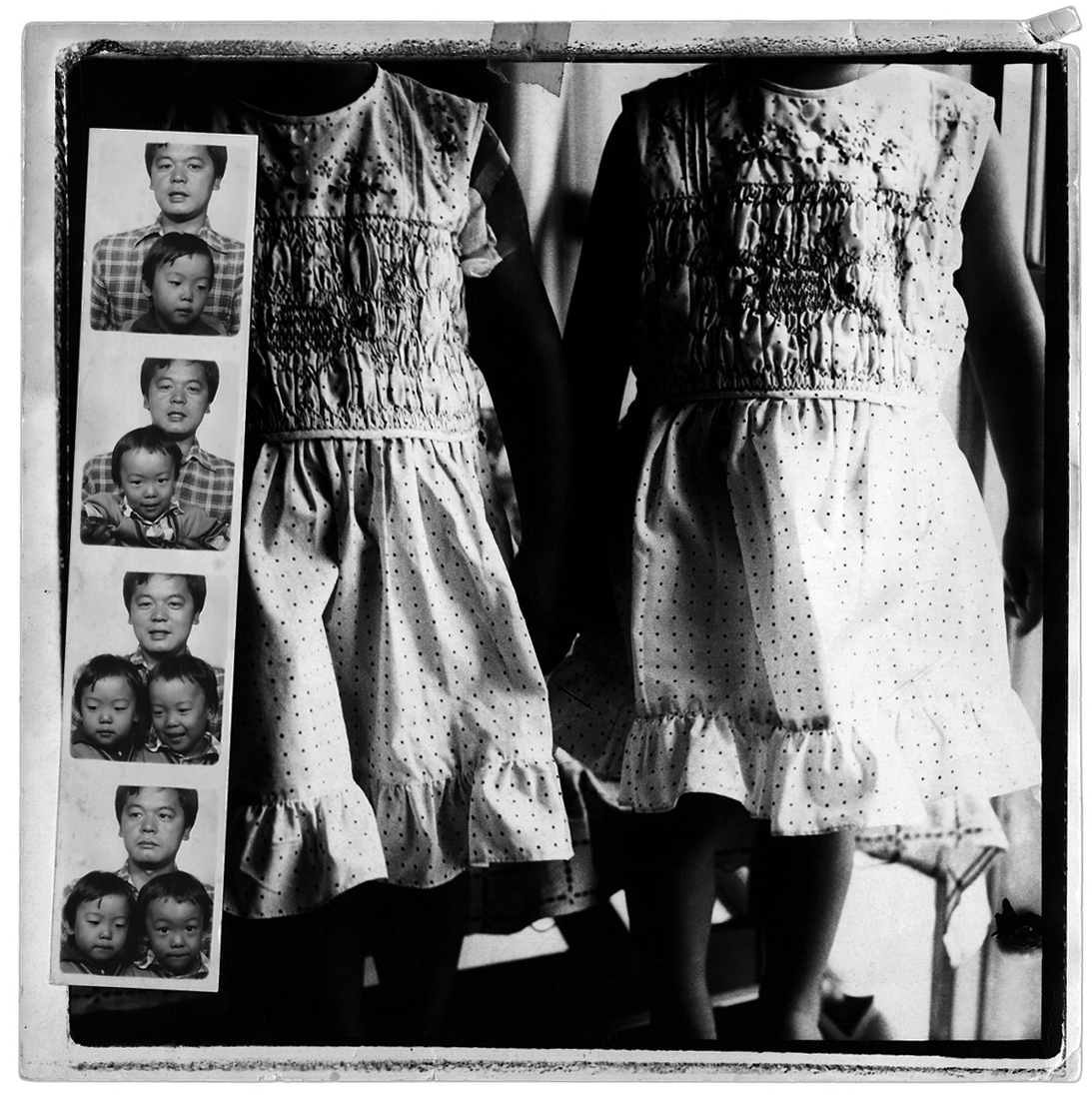

On the wall of Yoko's livingroom in Yokohama: Kiyoshi and their twin daughters Yu and Hikari

On the wall of Yoko's livingroom in Yokohama: Kiyoshi and their twin daughters Yu and Hikari

Kiyoshi Suzuki: Soul and Soul 1969 - 1999

Published by Noorderlicht in 2008 on the occasion of the Suzuki retrospective curated by Machiel Botman

Softcover with illustrated dustjacket, and (secretly) handstamped Japanese title in red ink, visible when removing the dustjacket. 80 pages in full color and black and white offset printing on uncoated paper. Seperate, stapled 14 page text booklet, with two text: The Happiest Moment by Yoko Suzuki and Layer upon layer upon layer by Machiel Botman. Further included is a biography.

Editing: Machiel Botman.

Design: Hans Miedema, with Ype van Gorkum, Marco Wiegers, Wim Melis, Olaf Veenstra and Machiel Botman.

Printed by Tienkamp & Verheij, Groningen

Binding by Patist, Groningen

Published by Aurora Borealis Foundation/Noorderlicht 2008

Acknowledgements: Kazuhiko Motomura, Shin Kajimura, Daido Moriyama, Elisa Uematsu of Taka Ishii Gallery in Tokyo, Magda Giacopini, Isoko Nagaoka, Yuko Ogura and Masao Okubo.

First edition 2008 - 1000 copies

Second edition 2009 - 1000 copies

Images of the work of Kiyoshi Suzuki and images of the spreads from Soul and Soul 1969 - 1999 are shown on this website with the kind permission of Yoko Suzuki and the publisher Noorderlicht.

(copyright for the images of Kiyoshi Suzuki is with Yoko Suzuki, copyright for the images of the spreads of Kiyoshi Suzuki: Soul and Soul 1969 - 1999 is with the publisher Noorderlicht. Use is strictly prohibited without permission)

Machiel Botman

Machiel Botman