Kazuhiko Motomura

Kazuhiko Motomura passed away

Many people will be touched by this

Such a beautiful man

Not long after I published my first book Heartbeat in 1994, I received a letter from Japan from Mr. Kazuhiko Motomura. It was a friendly letter telling me he had found my book in Tokyo and he asked if I would send him a dedicated copy. He would be happy to pay my price plus shipping, or he could propose a Japanese photo book in exchange.

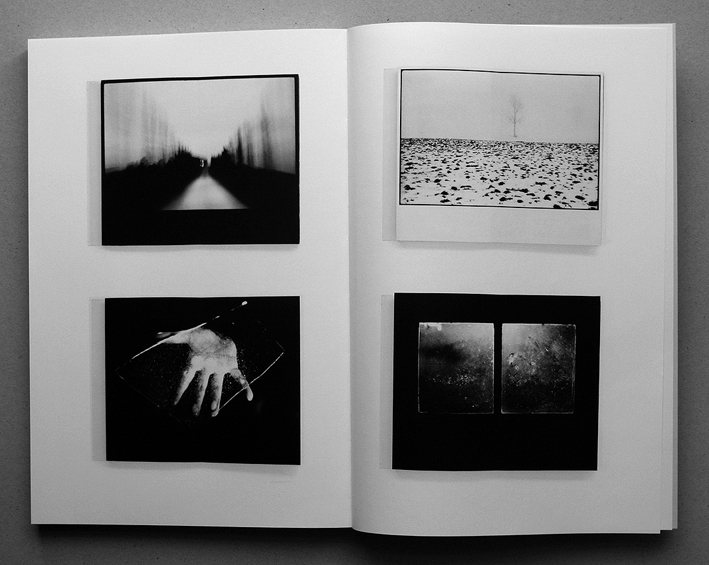

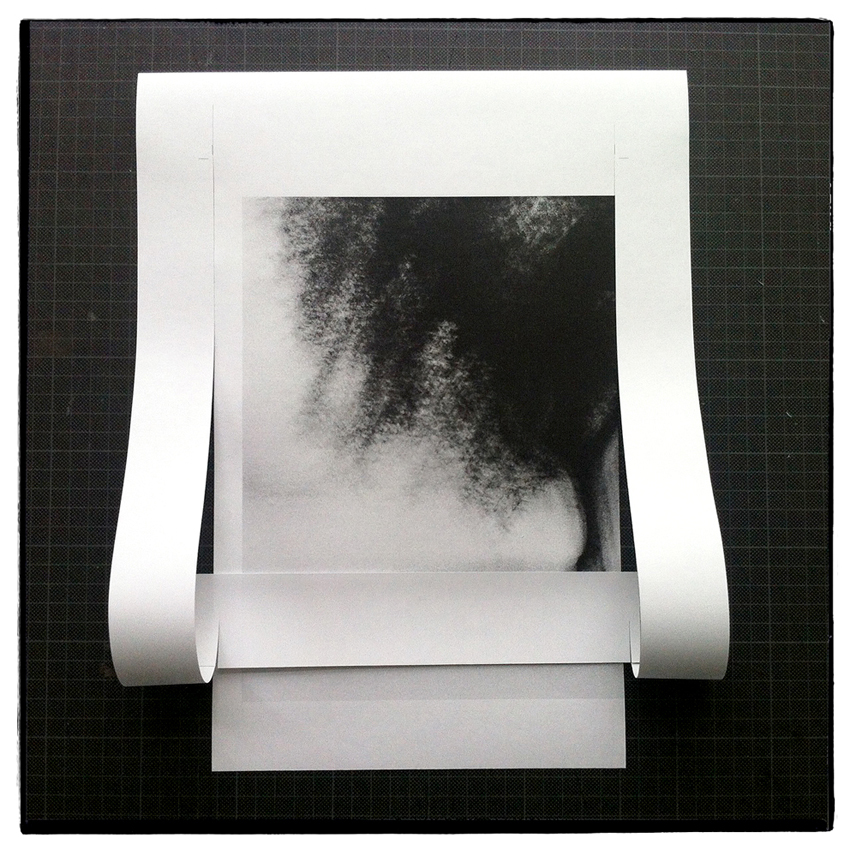

I sent him my book and received a Japanese book in return. At that point I had already entered the world of Japanese photography books and I knew who he was: the Japanese publisher who, in the early seventies, asked Robert Frank to do a book, which became The Lines of My Hand. Frank writes warmly about the visit by Motomura in one of the editions of this book. Motomura also published Frank's simply wonderful Flower Is, and he published Jun Morinaga's River, its shadow of shadows, which comes close to the most perfect meditative object.

The first book he sent me was Daido Moriyama's Inu no Toki from 1995, with work made in New York, Okinawa and Tokyo. Motomura had Moriyama dedicate it to me and in his fax he described the exhibition, the differences between the series and what Moriyama had told him about this work.

In 1995 conversations about photography books were still about the content of these books. It was about the photographs and the ideas they proposed and not about their pricing, their condition, their so-called innovative importance. We would go to the antiquarian bookstore, we would first check the section on countries, as it was there you could find La France de Profil by Paul Strand, William Klein's city books, Roman Vishniac's Polish Jews . . .

Motomura and I exchanged many, many books. First we kind of kept an eye on what we each spent, but we dropped that as we went along. I remember finding a copy of Dutch Details by Ed Rusha in a small Dutch town. Not really my thing, but I could see it was a strong and interesting book and told Motomura about it. The fax machine answered in two minutes, with a large YES handwritten on a piece of paper. I sent him all Johan van der Keuken's books, some books by Ed van der Elsken and Sanne Sannes, these being my favorites from my own country. Dave Heath, A Dialogue with Solitude; David Seymour, A Loud Song; Ken Schles Invisible City; Christer Strömholm Poste Restante; Anders Peterson Grona Lund and Ingen har sett allt . . . hardcovers of Vietnam Inc. by Philip Jones Griffith and The Destruction Business by Don McCullin - too many to recall. And in return he sent me known Japanese books, his own publications, and also many (to me) unknown Japanese books. There was one unexpected box with all eight titles by Kiyoshi Suzuki. I sat on my floor unpacking each one, happiness to the top !

We finally met in 1999 when I went to Tokyo to meet photographers who were going to be part of the exhibition Wonderland, for which I was guest co-curator. Noorderlicht in Groningen, produced this exhibition. Motomura had asked me to meet some photographers, like Jun Morinaga and Kiyoshi Suzuki. It was my first time in Japan and I spent three, four days going around, to galleries, museums, second hand bookstores, libraries and meeting photographers. Motomura had hired an interpreter, Gallery Mole was the central place, we spent from early morning to late evening together, I drank more than I ever had and ate little transparent fish, I believe it was to celebrate spring.

We met several times in the following years, in Japan and in Europe. On his request I introduced him to one of my dearest friends, the writer Catherine Duncan. They talked about Kate writing a text for the next book of Jun Morinaga. I had shown Kate Morinaga's River book, which touched her very much. She felt a connection with Paul Strand's photographs on his garden, the work she knew so well.

Motomura helped when Yoko Suzuki and I met to discuss doing a retrospective exhibition with Kiyoshi Suzuki's work, again with Noorderlicht. We had tea way up in one of Shibuya's skyscrapers, Shin Kajimura was helping with the language. Motomura sat there at this table, with smiling eyes and he said almost nothing. It was his presence that made us all feel safe.

How can you describe a man who is nothing but kind? Who is so important to Robert Frank, who at the same time pushed the work of many young photographers in Japan. He was always showing me someone's work - a small exhibition, a set of prints or a book dummy.

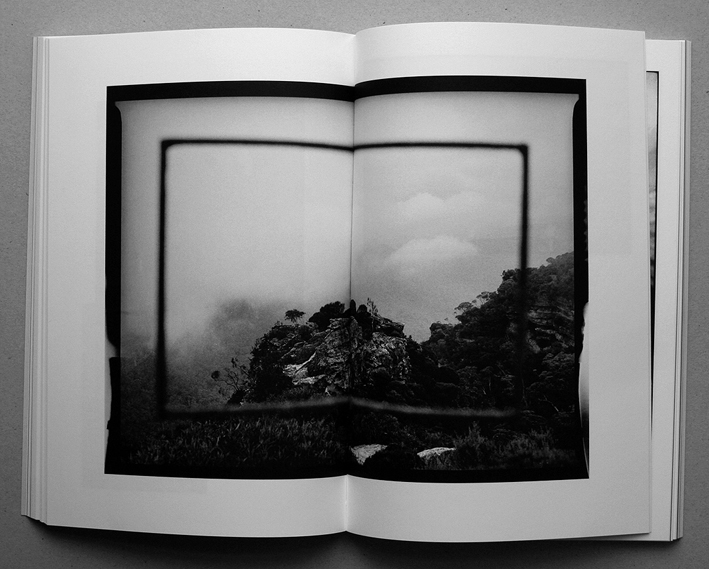

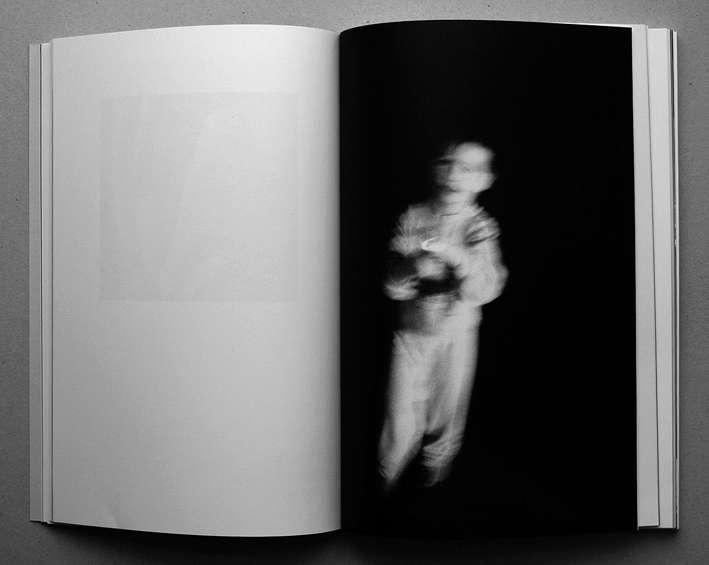

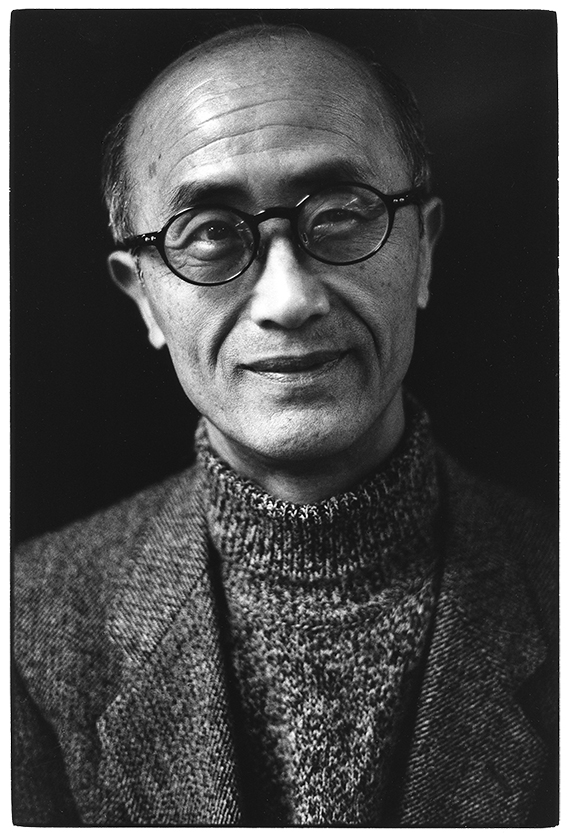

(Kazuhiko Motomura, in the library by Gallery Mole, Tokyo 1999)

It is strange we never understood each other's words while we talked. Until translated I could only guess what he said. By then it had mostly become practical. Perhaps we spoke with our eyes. One time in Amsterdam I had dinner with him, Jun Morinaga and Reinier, another close friend. There was nobody to help with the language; the conversation was about photo books, philosophy, the dinner, Kate. Now I realise it was mostly the personality of this one man that made all that possible. His presence alone implicated many layers of kindness and trust.

In recent years we had less and less contact. I wondered about him and his family and hoped everything was ok. I also wondered about his many friends, in Japan and around the world and I was sure everyone was missing him and wondering too.

Machiel Botman

Machiel Botman