Lidia, il cielo cade - Maurizio Cogliandro

Maurizio Cogliandro - Lidia, il cielo cade

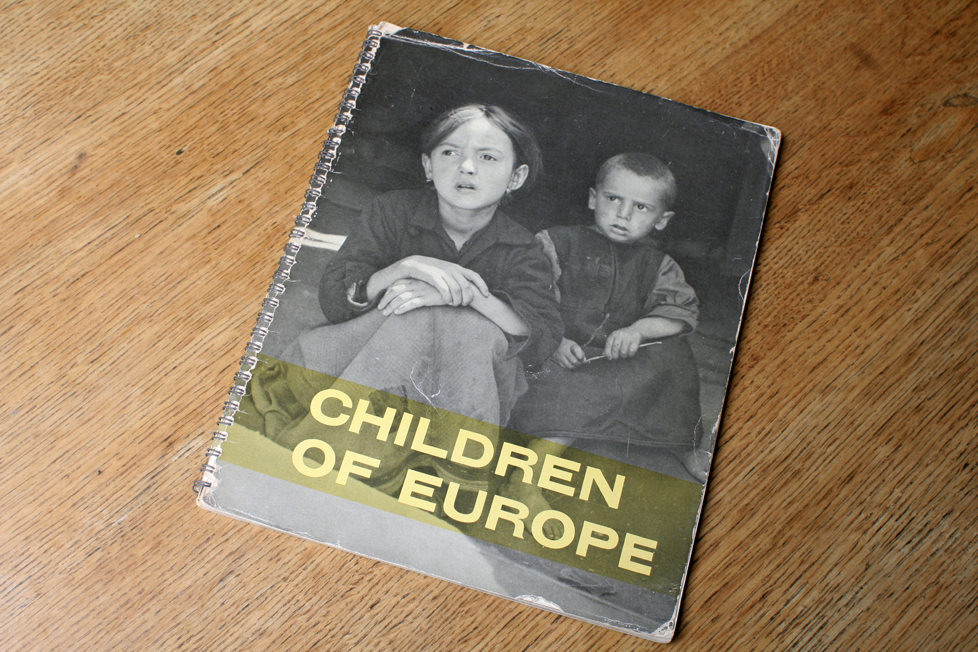

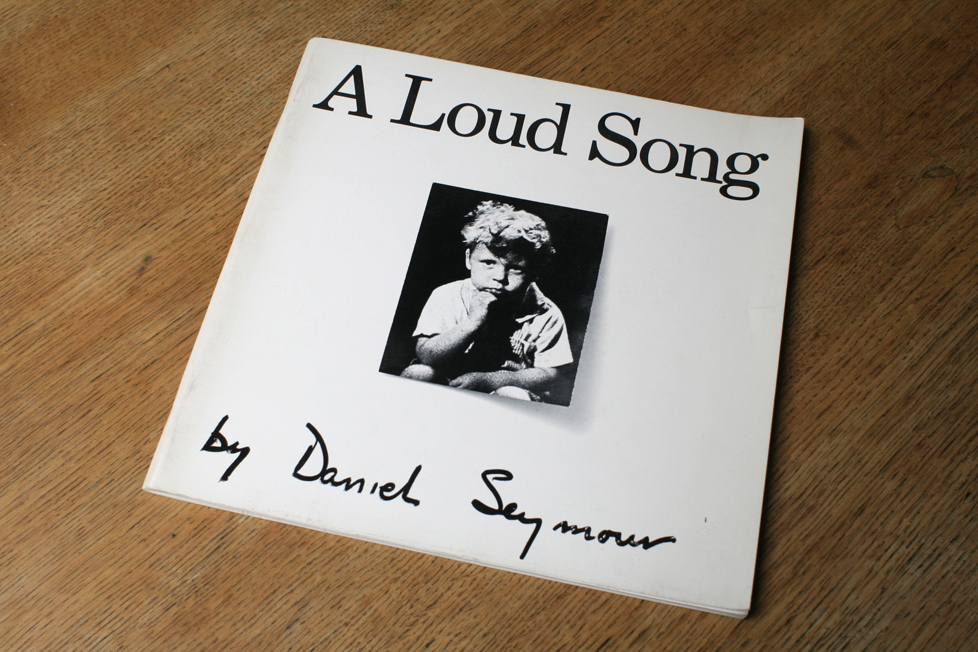

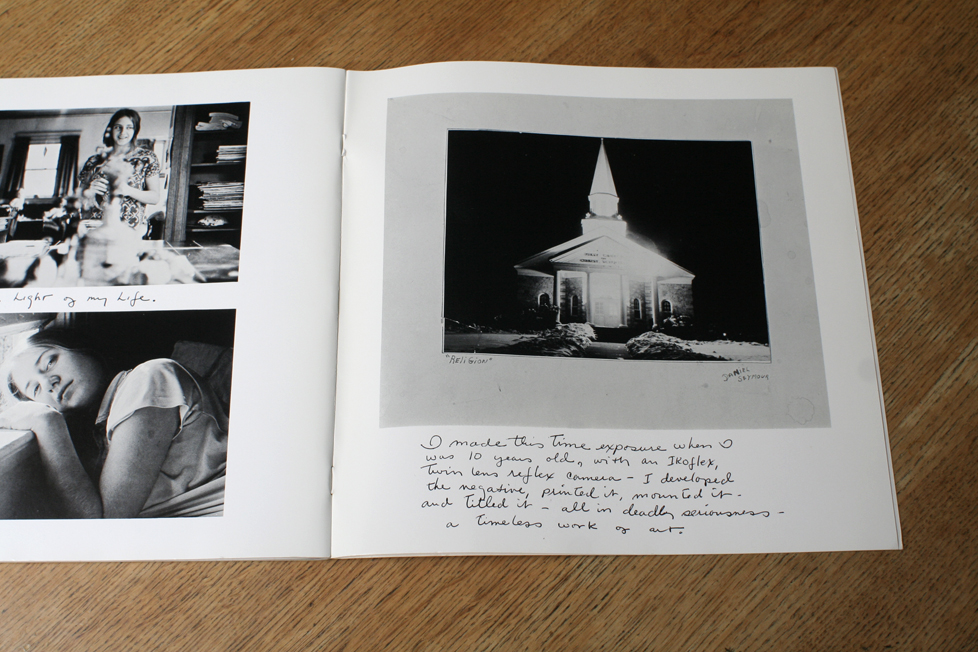

Lidia, the sky is falling. It does not happen often, but when it happens it is great. You take a photobook in your hands for the first time and, without opening it, you know it is a special book. It happened to me only a few times: with Children of Europe by David Seymour, the small ringbound paperback from 1949, with the yellow, imaginary band around the cover and the children's drawings on the back. It happened when finding A Dialogue with Solitude by Dave Heath, from 1965, with inside the blackest of inks showing an obscure tale of beauty and pain. With A Loud Song by Daniel Seymour, from 1971. The title and it's typography, the image on the cover and the last picture of the book (which so often we see first) of the church, made when Seymour was 10 year old . . . it was all there.

(David Seymour: Children of Europe, Unesco 1949)

(David Seymour: Children of Europe, Unesco 1949)

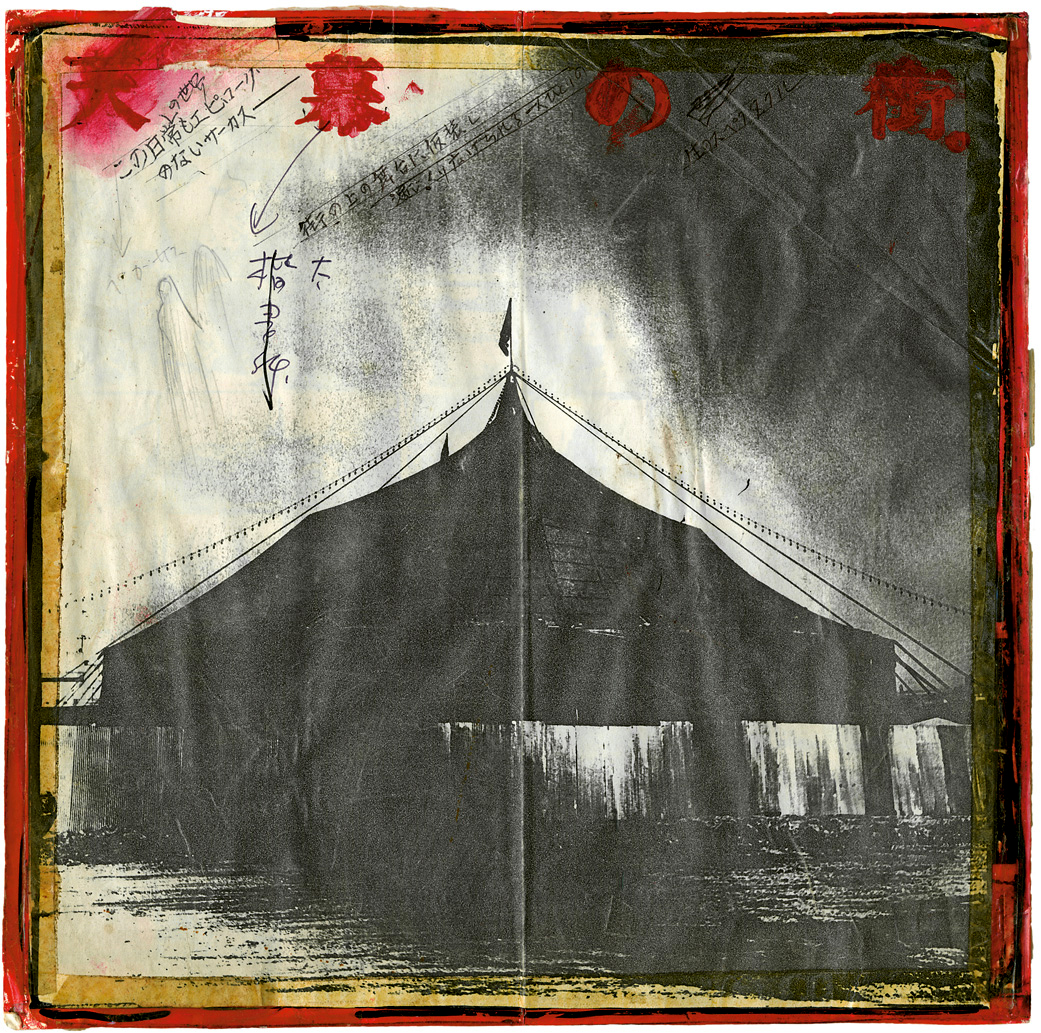

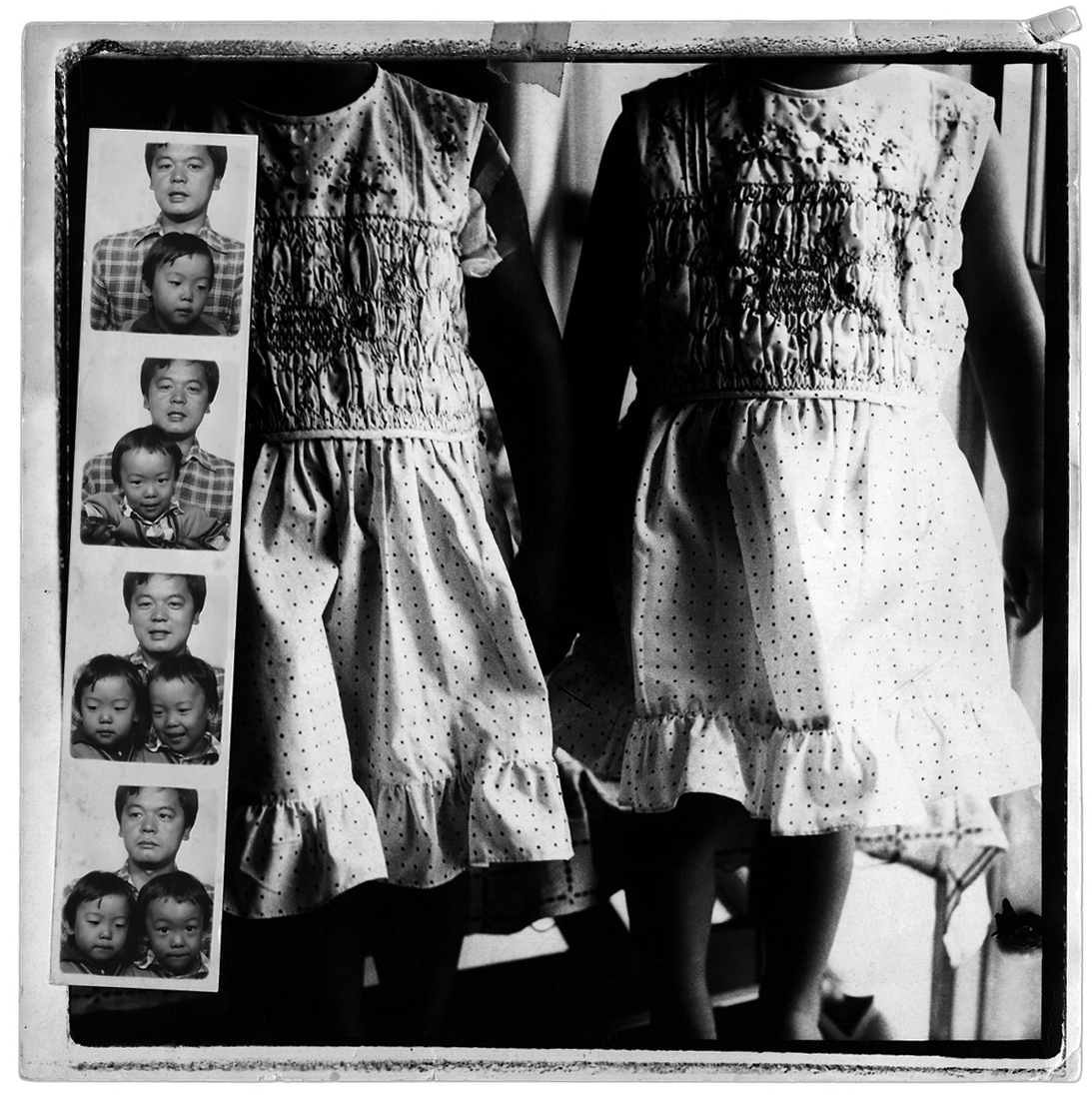

(Daniel Seymour: A Loud Song, Lustrum Press 1971)

(Daniel Seymour: A Loud Song, Lustrum Press 1971)

When, in the spring of 2010, I saw Maurizio's book first, it was from that 'first feeling' that I bought it right away. Contrary to what people believe of me, I do not buy many photobooks. I never have. It is just that over the many years I have constantly looked for and gotten, my favorites.

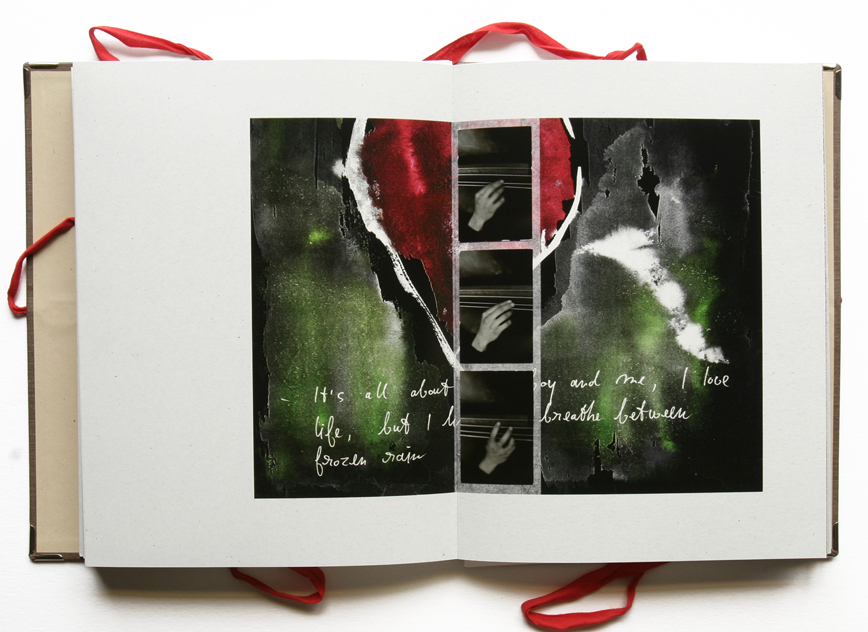

Lidia, il cielo cade is most of all a brave book because it shows losing a parent in a soft and quite 'normal' way. The emotions are unmistakingly there, but they remain between the mother, the father, the son and other family. We are left free to follow them all, quite close and in the most intimate moments, but we are never forced to feel the same pain. Of course when one carries similar pain, and both pains meet, then our breath is taken away and we face our own history. The sharpness of that confrontation, it's caracter, indicates to what extent we dealt with it all. Different stories from one to the other. But, at a certain point the acceptance stops, we need the pain, if only not to forget.

Miyako Ishiuchi photographed the skin of her mother not long before she passed away. And after her mother died, she photographed many objects in her mother's house. It was a gesture of saying farewell to her mother and this brought photography many icon images: the red and blue lipsticks, the hairbrush with still her mother's hair, the clothes. I saw those images more than ten years after my own mother died and they helped the pain still inside me, to shift to a safer place.

There is a sequence of four images in Lidia, il cielo cade: it is a simple story, Maurizo's mother takes her wig off, she places it on a headstand, she look at herself in the mirror and she has left the image. Perhaps she looks at the photographer, who stands behind her. Perhaps she sees her son, who stands behind her. I saw these images twenty years after my own mother died and still they helped the pain inside me.

Miyako Ishiuchi walked a solitary path where it concerned her mother. They hardly spoke until at the end of her mother's life. But then she passed away. My own mother's passing went too quick and was too unexpected, there was no shared path concerning her death. Maurizio was lucky. (sorry Maurizio!). There was some time and there was an understanding between him and his mother, to travel in the idea of making these photographs. Maurizio was fortunate in another aspect as well: he had around him some people who supported him and who helped him not to fall into the possible traps: of self pity, or of making something too 'right' or too 'easy'. I do not know everybody mentioned in the book, but I do know Laura Serani, Lorenzo Castore, Isabelle Darrigrand and Michael Ackerman. That is quite a group of mothers, sons, daughters and fathers.

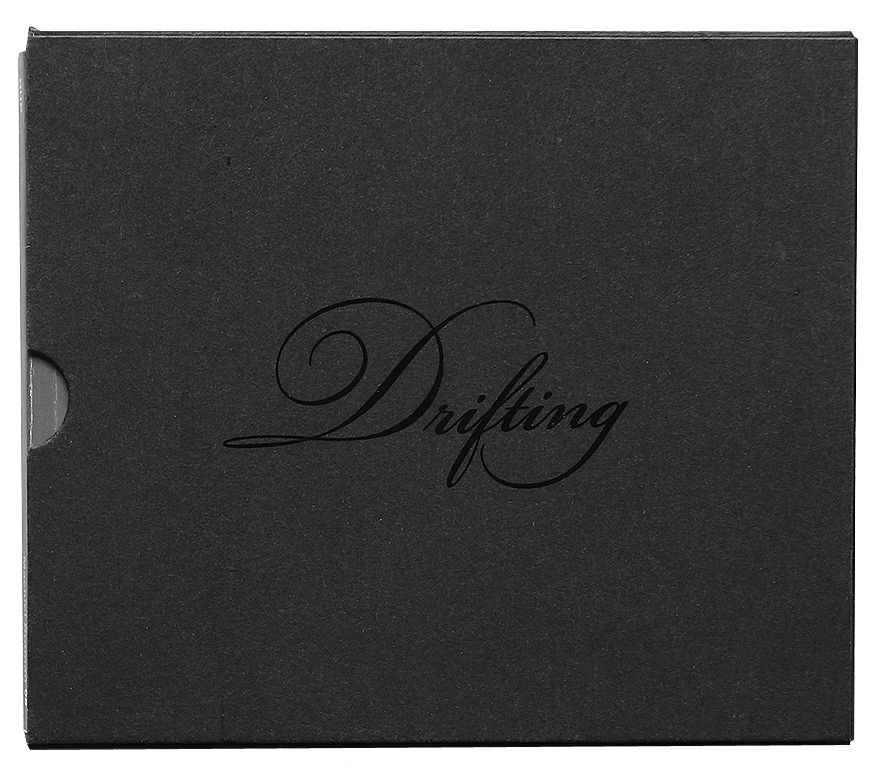

What determines that first moment of meeting the photobook?

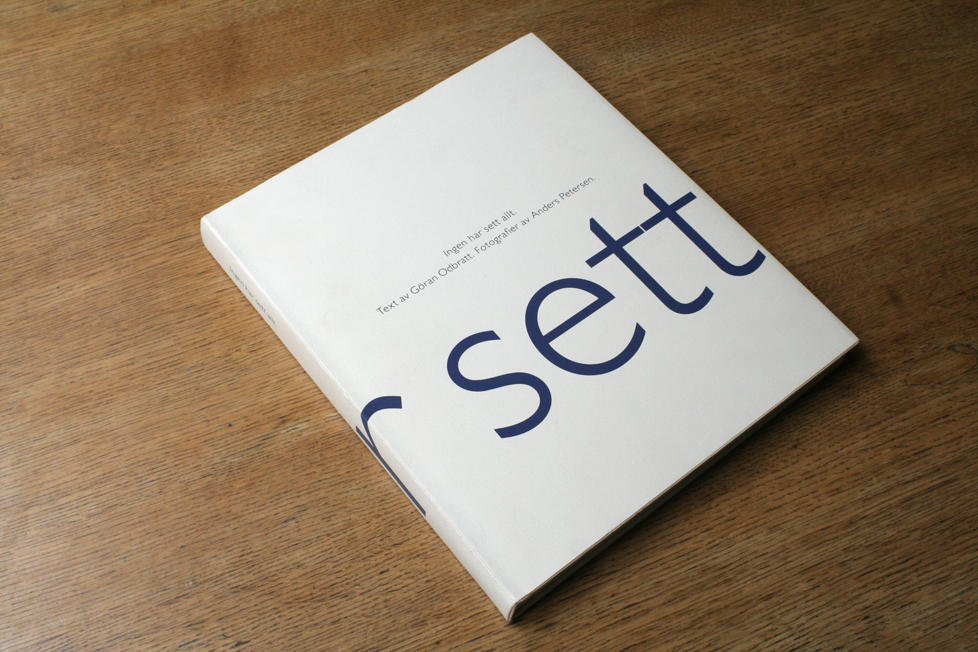

Perhaps my favorite book of Anders Petersen is Ingen har sett allt (Nobody has seen it all) from 1995. It's got his photographs made in a psychiatric home and they start halfway the book. The first half has a text by Göran Odbratt, in Swedish. I can't read it but I am convinced the text is as good as the photographs. One of the reasons why I am convinced about that is how the book was made, the object. Surely there is nothing light about this place, or about the images. And probably there is nothing light about this text. But this book object is totally light: the white cover, the dark blue typography, the spacing of the words on the jacket, the design of the text and the duotone printing: deep and transparent at the same time. Just like Anders.

(Anders Petersen: Ingen har sett allt, Legus Förlag 1995)

(Anders Petersen: Ingen har sett allt, Legus Förlag 1995)

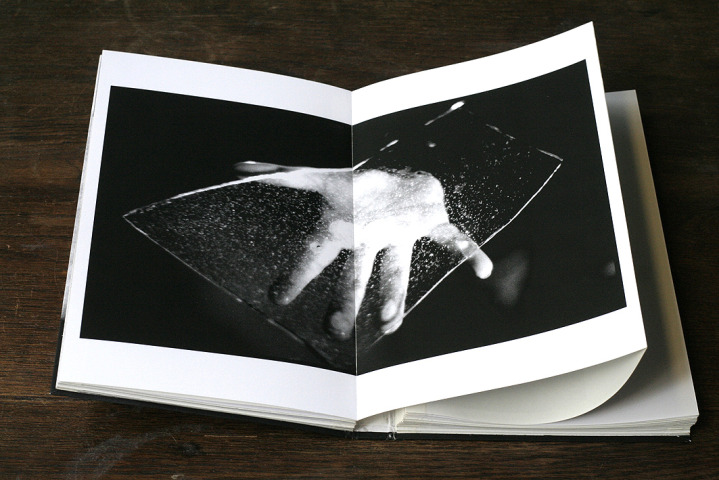

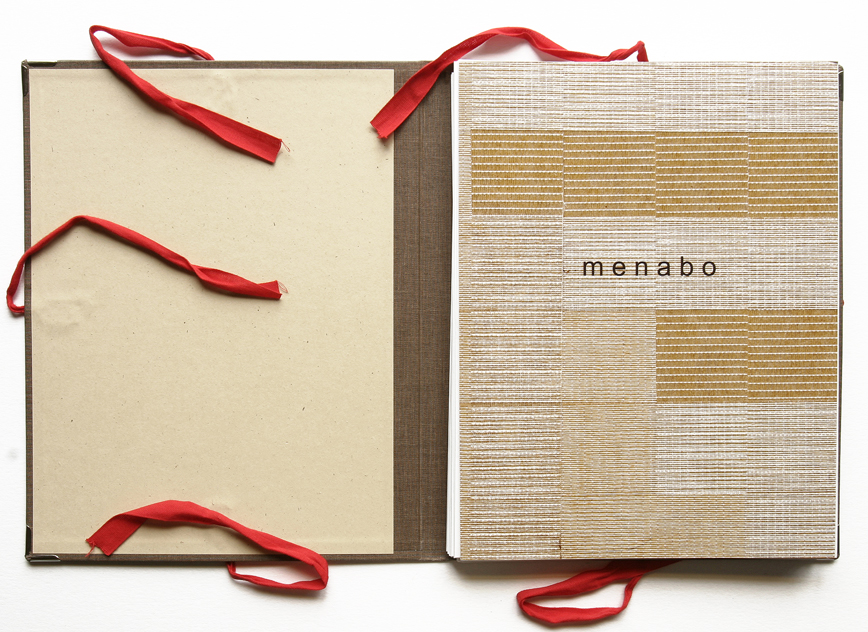

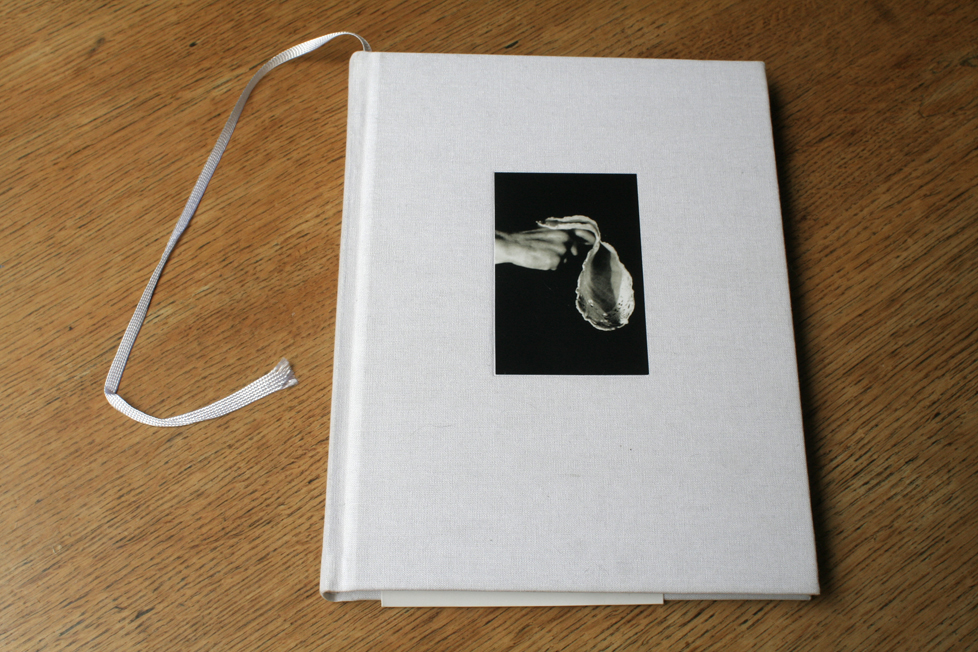

Maurizio Cogliandro must have thought along the same lines: Lidia, il cielo cade's cover is white linnen with a small photograph on the front. The layout of the images is very simple, one never feels a designer at work. Also this book breathes a certain lightness. Unusual is what is folded around the back cover: a stiff text band that is fixed together with tape on the inside of the cover. It first looked to me as an irritating invention of the publisher. But I got used it and kind of like it.

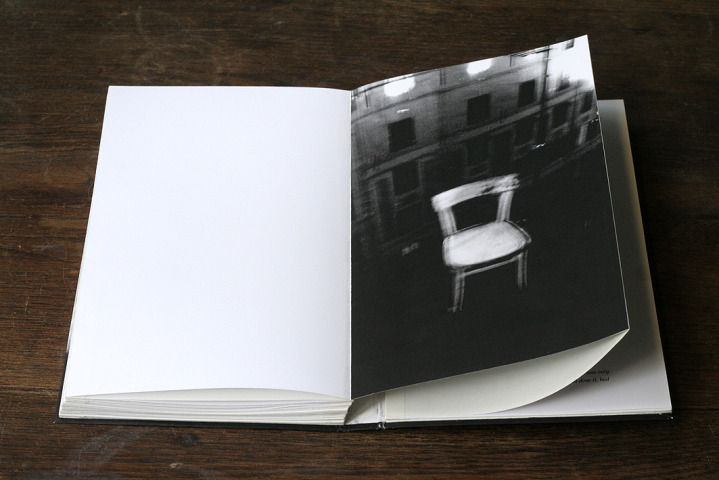

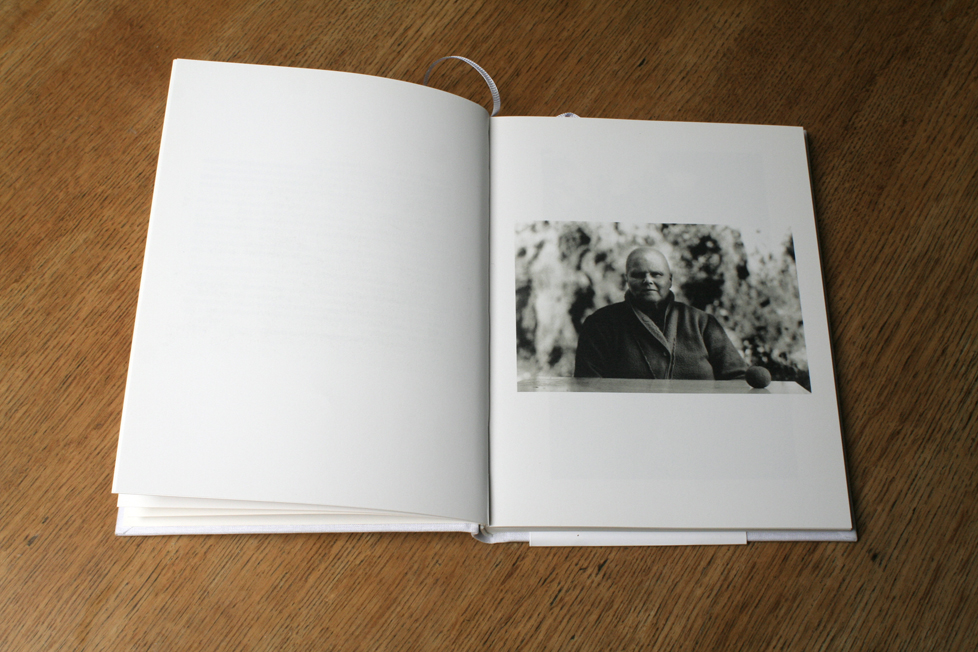

Lidia, il cielo cade speaks of the inevitable loneliness we meet when someone we love is dying. It does so in a sober and quiet way, with respect and without anything sentimental. The book is strong when the mother, in her eyes, comments on this son, the photographer. It is one of the first images in the book, she sits at a table, there is an apple lying there. If we assume this is in Rome, then it must be winter. An apple in winter. She has lost her hair and looks at the son with a beautiful intimacy. This image gives direction to the whole book, to the whole idea of the book and it stands out in Italian photography: it is truly personal.

The book is non-linear, with the images are no names, no dates, no places, no chronology. In that way it also stands out: it does not attempt to spoonfeed us what is obvious. After opening the book's cover the lights simply go on, and when we close the book, the lights go off. In between are mother and son, keeping the light on for those around them, and for us. Until we close the book.

Lidia, il cielo cade - Lidia, the sky is falling

Published by Edizioni Postcart, in Rome 2010

Photographs and text Maurizio Cogliandro

Design Maurizio Cogliandro and Claudio Corrivetti

English translations by Valentina Nobili

Printed by CDC Arti Grafische

cogliandromaurizio@gmail.com

info@postcart.com

The images of Lidia, il cielo cade are published here with kind permission of both photographer and publisher. The copyright of these images is with the publisher and the photographer - no reproductions without permission.

Machiel Botman

Machiel Botman